Tackling the Plastic Pandemic by Closed-circuit Television Monitoring

(This story was originally published at the CounterMEASURE project website on November 30, 2021)

“I had thought that we would see garbage from a household, so I was completely shocked to discover medical masks, gloves etc., instead. Unfortunately, this is not the only case of its kind, and this is just the tip of the iceberg! I feel terribly disconcerted as I realise that the Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) kits used for fighting the pandemic, has now become a major part of the litter polluting our precious Mekong River,” said Kavinda.

Above: “Strange object” floating into the port in Chiang Rai; Below:: Medical masks, gloves, COVID-19 test kits found in the Mekong River.

While we are still moving towards overcoming the COVID-19 pandemic, we can’t ignore an increasing problem that the fight against the virus has worsened. Plastics have been deployed in great quantities as a primary shield against the pandemic. But little attention has been paid to where increased plastic waste will end up. The sad irony is we were on the cusp of real victories against plastic pollution just as the coronavirus pandemic began.

Plastics, especially single-use plastics, became more ubiquitous in 2020 and 2021 around the world. Masks, sanitizer bottles, personal protective equipment, food packaging, water bottles, retail goods – our lives are almost wrapped in plastic now!

Accumulation of plastic wastes in Mekong River

The Mekong River, the largest international watercourse in Southeast Asia, is the lifeline of hundreds of millions of people in Southeast Asia. But the river also carries the most plastic into the world oceans. Southeast Asia is considered a major contributor of global plastic pollution, as Asian rivers may release up to 86% of the global annual plastic input into the oceans, especially during the East Asian monsoon (Jambeck et al 2015, Lebreton et al 2017, Schmidt et al 2017; Charlotte, et al, 2021).

Understanding how plastic flows into the Mekong is key to solving the problem of marine litter. This is what inspired researchers from GIC to setup the camaras on a Mekong port in Chiang Rai, northern Thailand in November 2021 as part of UNEP’s efforts at solving the problem of plastic pollution by monitoring the types and amounts of plastic flowing into the Mekong River.

CCTV installed at the Mekong port in Chiang Rai, northern Thailand

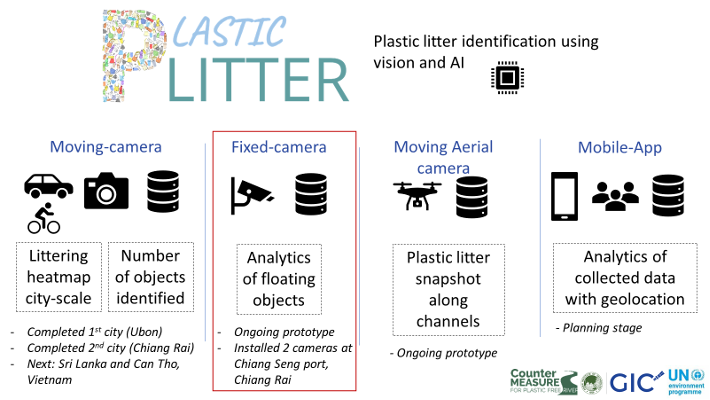

This CCTV-based monitoring system started as a prototype study under the “pLitter”, a tool developed by GIC-AIT under CounterMEASURE funded by the Japanese Government, to tackle plastic pollution using AI and other cutting-edge technologies. This initiative uses several innovative digital tools to identify plastic hotspots along the streets and waterways. One of those technologies is a vehicle-mounted camera that detects plastic litters along the streets and produces plastic litter heatmaps. A mobile application is also used to detect plastic accumulation hotspots by local stakeholders such as project partners and community scientists (click here for a live feed of the data collection dashboard). This prototype will be completed by the end of Feb 2022 and presented in the project closing workshop.

The CCTV project has already been shared with the Mekong River Commission Secretariat (MRCS) to contribute their development of the regional protocols on plastic pollution in the CounterMEASURE project. Thorough MRCS, this protocol will be adopted by each member countries including local governments.

An important goal of the CCTV project is to contribute to policy development against plastic pollution in each region with the help of its findings.

Dr. Kavinda elaborated on the expected results of the CCTV monitoring saying, “The installed CCTV systems are connected to a cloud system and feed the data to an AI model to train to predict the floating plastic litter. We will be able to detain the floating plastics litter and raise awareness to reduce littering rivers. The team is developing this as a low-cost module that could easily replicate or improve further, and all the guidelines will be published at the end of the project.

An interesting fact is that after the CCTV installation, Dr. Kavinda showed the CCTV footage to his children aged 7 and 4 years. His young children even understood how bad it is to throw garbage into rivers and showed concern and curiosity regarding reducing the waste. This was a clear testimony about how CCTV footage can create awareness and bring about behavioral change.

Use of the CCTV technology and image processing with the AI is supported by UNEP’s CounterMEASURE project. “The project hopes to gain new insights into plastic leakage hotspots and pathways along rivers in Asia such as the Mekong to better inform policy and decision-making processes to beat the plastic pandemic.”, said Kakuko Yoshida, UNEP Global Coordinator of Chemicals and Pollution Action. “We need more innovation, technologies, and citizen support to deepen our understanding about the problem as the first step to a solution.”

Sunrise at the Mekong River